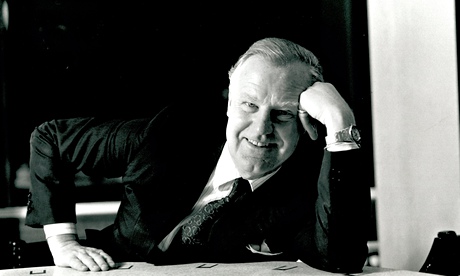

A H Halsey – obituary

A H Halsey was a socialist academic who believed that comprehensive schools were the key to an equal society

Professor A H Halsey, who has died aged 91, was Britain’s first Professor of Sociology and played a key part in the 1960s, as adviser to Anthony Crosland, the Labour education secretary, in the switch to comprehensive education.

Chelly Halsey, as he was always known, was one of the last relics of the Labour academic generation that came up the hard way. But, although he himself had enjoyed a grammar school education, he believed that only the abolition of selection could bring about true equality. He was unapologetic about his belief that education should be used as an instrument in pursuit of an egalitarian society.

Halsey saw himself as an ethical socialist marching in the wake of such figures as William Temple and R H Tawney. Although he rejected revolutionary Marxism, he believed that the truth of socialism would be proved by empirical research, and that laying bare the facts would inevitably move the British people to eradicate inequality. “For me personally,” he wrote, “the class system, whether in its inherited rural form of squirearchy or its urban structure of bourgeoisie and proletariat, was always anathema.” It had to be rooted out — by force if necessary — using the tools of progressive taxation and compulsory comprehensive education.

Whether or not it ever truly existed, he was incurably nostalgic about the working-class England of the pre-war era, describing himself as a “pilgrim” who believed that “the institutions invented by the Victorian and Edwardian working class — the Unions, the Cooperative Society and the Labour Party — were the route to the New Jerusalem”. In an introduction to Twentieth-Century British Social Trends (2000) he evoked some of those qualities he missed so much, approvingly quoting George Orwell: “The crowds in the big towns, with their mild knobby faces, their bad teeth and gentle manners.”

To his critics he was that most dangerous of political animals, a puritan romantic — someone who by his own admission believed in the “overwhelming importance of collective as distinct from individual experience and consciousness”. For what always seemed to be missing from Halsey’s egalitarianism was an understanding of the competitive side of human nature.

In 1974 he provoked widespread ridicule when he appealed to parents to remove their children from public schools on the ground that they were contributing to the deprivation of disadvantaged children. More reasonably, he strongly disapproved of socialists who “suddenly found exceptional reasons to send their children to non-comprehensive schools” (as well as those who accepted membership of the House of Lords).

The experience of being Crosland’s adviser was not entirely happy. Crosland, in Halsey’s view, was a disappointing minister who ducked the important decisions that needed to be taken, like abolishing the public schools. As a practical politician, Crosland balked at the idea on grounds both of individual liberty and political unpopularity. Halsey, the idealist, saw no conflict between the goals of liberty and equality and did not acknowledge the political problem.

A H Halsey

Crosland also represented a strand of 1960s liberal socialism that was alien to Halsey. Indeed, it was only Crosland’s commitment to comprehensive education that enabled Halsey to overcome his distaste for the man himself — “a profligate drinker and philanderer… alcohol, cigars, women, even opera were avidly consumed”, as Halsey recalled.

In later life, Halsey bemoaned the loss of old moral values and the breakdown of the traditional ties of family and community. But like many socialists of his generation he tended to blame society’s ills on Thatcherism, rather than on the egalitarian socialism of which he had been a prominent exponent.

The second of nine children, Albert Henry Halsey was born in Kentish Town on April 13 1923 into a patriotic Christian socialist family. His memories were of a wholly manual inheritance. His father was a railway worker and his wider family comprised hordes of skilled uncles and aunts. This early upbringing shaped his whole life. “I cannot pretend to be other than puritanical in my attitudes towards work and leisure and life,” he once admitted. “The manual uncles always haunt me, investing the stint with sacred quality.” The titles of some of Halsey’s major works reflected this early background: Social Class and Educational Opportunity (1956); Educational Priority (1972); Heredity and Environment (1977); Origins and Destinations (1980); and English Ethical Socialism (1988).

When Chelly was still an infant, the family moved to Lyddington in Rutland, then to a council estate at Corby, Northamptonshire. There they eked out a meagre income by foraging for blackberries and mushrooms and befriending the local poachers. A defining moment of Chelly’s life came when a tramp appeared at the kitchen window and stretched out his billy-can. Chelly’s mother gave the man tea and two thick slices of bread and dripping. “God bless you, Missus,” said the tramp. “Good luck to you, mate,” his mother replied.

Halsey won a scholarship to Kettering Grammar School and stayed on in the sixth form to take the exams for the clerical grade of the Civil Service. When these were cancelled at the outbreak of war, he left school aged 16 and worked as a sanitary inspector’s apprentice at £40 a year. On his 18th birthday he volunteered for active service and entered the RAF as a pilot cadet. He trained as a fighter pilot in Rhodesia and South Africa, perfecting the “aerial handbrake turn” that, he hoped, would keep him out of the way of Japanese Kamikaze pilots. He never met the Japanese in action but nearly lost his life when, practising the manoeuvre, his plane took a nose dive, recovering only yards from the ground. By the time the war ended he was a flight sergeant in the RAF medical corps.

It was the offer of further educational opportunities to men in the Armed Forces that gave Halsey his opportunity to acquire a university education. After demob, he enrolled at the London School of Economics. It was there that he met, and in 1949 married, Margaret Littler, a fellow student.

After graduating from the LSE, he took up research work in Sociology at Liverpool University then, in 1954, became a lecturer in the subject at Birmingham. In 1956-57, he took a sabbatical year in America, working at the Center for Advanced Study of the Behavioural Sciences at Palo Alto. It was at Birmingham that he undertook the work that underpinned the Labour Party’s early commitment to comprehensive education. In his first major study, Social Class and Education (with J E Floud, 1957), he explored the relationship between social class and success at 11-plus, concluding that working-class children were disadvantaged by the selective system.

In 1962 he left Birmingham as senior lecturer to become head of Barnett House, Oxford University’s department of social and administrative studies, and a professorial fellow of Nuffield College. Sociology was rather frowned upon at the time, but Halsey fought successfully to establish it as part of the academic mainstream. He became Professor of Social and Administrative studies in 1978 and also participated in university governance, serving on Oxford’s Hebdomadal Council. He devoted two books, The British Academics (1971) and The Decline of Donnish Domination (1992), to academic affairs.

Crosland appointed him his adviser on education in 1965, but after Crosland’s departure in 1967 Halsey found himself cold-shouldered by his successors. Patrick Gordon Walker made him feel like “Charlie Chaplin in City Lights where a toff would get drunk and take Charlie home, swearing eternal comradeship, and then have him thrown out in the morning as a person unknown”. Ted Short was “not much better”. Shirley Williams ignored him completely.

Surprisingly, Halsey was called upon by Mrs Thatcher in her role as education minister in the early 1970s to advise on nursery education, though she never acted on his recommendations that more money should be poured into deprived “educational priority areas” and nursery education. In the 1980s he emerged as one of the main opponents of Mrs Thatcher’s being given an honorary degree by Oxford, arguing that the university should “stand up for education against its principal oppressor”.

In 1983 he was a major contributor to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Commission on Urban Priority Areas whose report, Faith in the City, was widely dismissed by Conservatives as little better than socialist propaganda.

Not that Halsey had much time for the other political parties at this time. While he hated the extremists in the Labour Party, he disliked the breakaway Social Democrats even more, dismissing them as “middle-class Oxbridge intellectuals” whose party allegiance “did not come from childhood experience of the daily struggle that informed the politics of my own kith and kin”.

But by one of those strange quirks of politics, after his retirement in 1990 Halsey found common cause with thinkers on the Right about the disastrous effect of permissive attitudes on social cohesion. In Families without Fatherhood, which he co-wrote, and which was published in 1992 by the normally Right-wing Institute for Economic Affairs, he drew attention to the link between crime and family breakdown, harking back to “respectable” working-class family life just before and after the war, when the heart of the family was stable marriage, which anchored men into the child-rearing process.

Later the same year he criticised the way in which women had been betrayed by feminist demands for equality. Women, he felt, were now worse off than at any time since the suffragette movement because they were combining the role of breadwinner with mother.

Not surprisingly, he displayed a profound scepticism for the Islington radicals of New Labour. In a passage in his autobiography (No Discouragement, 1996), he recalled an exchange with Tony Blair over dinner in 1995. They were getting on reasonably well until Blair suddenly asked who the second most interesting character in the New Testament was and gave as his own answer Pontius Pilate.

To Halsey this was “a characteristic politician’s choice”, and he did not disguise his disapproval. His own selection, perhaps equally predictably, fell on the Good Samaritan as “a member of a despised minority engaged in direct action”. Clearly not wanting to get into deep waters, Blair immediately backtracked, remarking that, naturally, the last person he would try to emulate in power would be Pilate.

In 1977 Halsey was the BBC’s choice as its Reith lecturer. In retirement, he enjoyed gardening and woodwork, but he also continued writing. His later books included A History of Sociology in Britain (2004), followed by Changing Childhood, a history of the Halsey family, in 2009, and Essays on the Evolution of Oxford and Nuffield College in 2012.

His wife Margaret died in 2004; he is survived by their three sons and two daughters.

Professor A H Halsey, born, April 13 1923, died October 14 2014

George Monbiot (Life in the age of loneliness, 15 October) does not refer to the role that our planning system has played, at least as an accomplice, in creating the loneliest “society” in Europe. During the next few years hundreds of thousands of new homes will be built, mostly following a model that could reasonably be described as “pandering to privacy”. In 1968 an American sociologist, Philip Slater, suggested that: “The longing for privacy is generated by the drastic conditions that a longing for privacy produces.” We seem to be in this vicious cycle where our individualism makes it increasingly difficult to provide mutual support and affection. Private housing is being designed to be not only privately owned but anti-social in its occupation. Planners should be engaged in the provision of co-housing where care and companionship are the norm.

Daniel Scharf

Abingdon, Oxfordshire

• Reading George Monbiot, I was surprised at the unwarranted and unexplained attack on TV. The WaveLength charity has supplied TVs and radios to lonely and isolated people living in poverty since 1939. We know TVs and radios ameliorate loneliness through the “social surrogacy hypothesis”, an effect studied by researchers at the universities of Haifa, Buffalo and Miami.

Monbiot is absolutely correct that loneliness is a scourge of our time and a leading contributor to poor mental and physical health. However, his depiction of TV as a “hedonic treadmill”, ranged on the side of selfish aspiration, jars with our experience of TV as one of very few supports left to isolated people – as well as the most accessible form of culture.

TVs and radios give WaveLength’s users something to talk about with family, friends and carers, as well as providing friendly faces and voices when they’re at their lowest. In day centres, homelessness hostels and women’s refuges, TVs become focal points for residents to meet.

Some of our users’ loneliness stems from the societal factors Monbiot describes: families dispersed to follow work, irregular public transport, erosion of pubs and cinemas. But others – living with illnesses or disabilities, struggling with addiction or escaping domestic violence – are less able to cope with regular socialising. TVs and radios give them comfort and a sense of structure when getting outside is difficult. No one would deny the painful effects of loneliness. But WaveLength’s 75 years in operation shows that isolated people have always appreciated media technology’s ability to keep their windows to the world open.

Tim Leech

Chief executive, WaveLength

• I was immensely moved by the article (Family, 11 October) about the upcoming film Radiator in which Tom Browne reflects on how he found himself trying to change his elderly parents’ lives. It rings so true with my experiences. I recall one day when I went to see my mum some time after my 95-year-old dad had died. He had survived a stroke for 10 years and in that time never left the house, and they bumped along, refusing help. I knew mum and dad always liked Wimbledon, so I turned up with scones and strawberries and made a lovely cup of tea and spread it before us. My mum watched the tennis for about five minutes, picked up the remote and put Emmerdale on. For 10 years, the soaps had rescued her from her mundane life and given her something to look forward to. I actually argued with her about turning it over. I should have taken my scone and tea and a radio and listened to the tennis in the sun in our lovely back garden in the house we had lived in for 60 years. It would have been great. I spoilt it for both of us. How I agree with Tom; we should give our parents what they enjoy and want, not what we think they “need”.

Debbie Cameron

Manchester

• One of the impacts of older people being referred to as a burden (Society Guardian, 15 October) is that older people themselves start to internalise ageist views which can lead to the loneliness and depression described by George Monbiot. Ageism is rife in society, and this may be compounding problems of depression, isolation and anxiety. Many older patients I see say things like “I’m past my sell by date”, “I’m too old to be helped” and “It’s too late to change”, leading them to give up doing things they could still do, and to be pessimistic about life as an old person.

Yet we know that those who stay involved and active live longer and happier lives. Treating all these older people with drugs or therapy is not the right solution. We need as a society to re-evaluate what age offers and to encourage healthy ageing across the life cycle. We have started a campaign in our area called “Proud to be Grey”, challenging ageist beliefs and encouraging people to carry on doing whatever they enjoy throughout their lives. Initially this has been a poster campaign across all council, mental health and GP settings, featuring local residents with three statements about things they enjoy about growing old. These have ranged from roles such as being a grandparent to activities they enjoy.

Dr CI Allen

Consultant clinical psychologist, Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust

• There would rightly be an outcry if any other group, such as women or an ethnic minority, was described as a burden. Age UK says that a third of pensioners do voluntary work. A further third of them do unpaid child-minding of their grandchildren so that their parents can work. Many of the over-60s look after their own elderly parents who are in their 80s. Older people are net contributors to society. Research carried out for the charity WRVS reveals people of 65 and over are also net contributors to the economy. Taking into account older people’s tax payments, caring responsibilities and volunteering, people aged 65 and over contribute £40bn more to the economy than they receive in state pensions, welfare and health services. By 2030 older people’s net contribution is projected to increase to some £75bn.

Ann Wills

Ruislip, Middlesex

• Loneliness among our elderly population is rife (Number of severely lonely men over 50 set to rise to 1m in 15 years, 13 October). The report by Independent Age and the International Longevity Centre-UK highlights the shocking extent of the problem – and how it’s set to get worse. Many people are unaware of the impact of loneliness on physical and mental health, and more needs to be done to widen awareness and address the problem. We’re supporting some truly inspirational charities that are addressing this issue locally, such as the Dorcas Befriending Project in London and Men In Sheds in Milton Keynes, and matching the first £10 of all donations made through Localgiving.com in our “Grow Your Tenner” fundraising campaign, just launched by the new minister for civil society, Rob Wilson.

Stephen Mallinson

Chief executive, Localgiving.com

If the taxi driver quoted in John Crace’s sketch (I’m David Farage, 17 October) is correct that Rochester is “the arsehole of Kent”, what does this make the politicians passing through?

Edward Rees QC

Doughty Street Chambers, London

• Re “The juvenile thrills of a puff in the park” (G2, 16 October): I presume the tigers in Trafalgar Square referred to are the ones under Napoleon’s Column.

Sally Howel

London

• Does the bronze of David Cameron on a bike (Secretive club hosts Tory fundraiser in aid of marginal seats, 17 October) come with a bronze of a limo carrying his papers?

Martin Berman

Glasgow

Tomorrow afternoon a memorial service will be held for David Haines, one of the three Britons kidnapped by Isis in Syria. David and Alan Henning travelled to Syria to help their fellow man by delivering vital humanitarian support to those who needed it most. Their desire to help was not driven by their religion, race or politics, but by their humanity. David and Alan were never more alive than when helping to alleviate the suffering of others. They gave their lives to this cause and we are incredibly proud of them.

We are writing this letter because we will not allow the actions of a few people to undermine the unity of people of all faiths in our society. How we react to this threat is also about all of us. Together we have the power to defeat the most hateful acts. Acts of unity from us all will in turn make us stronger and those who wish to divide us weaker. David and Alan’s killers want to hurt all of us and stop us from believing in the very things which took them into conflict zones – charity and human kindness. We condemn those who seek to drive us apart and spread hatred by attempting to place blame on Muslims or on the Islamic faith for the actions of these terrorists.

We have been overwhelmed by the messages of support we have received from the British public and others around the world. We call on all communities of all faiths in the coming weeks and months to find a single act of unity – one simple gesture, one act, one moment – that draws people together, as we saw in Manchester last week and as we are coming together in Perth today. We urge churches, mosques and synagogues to open their doors and welcome people of all faiths and none. All these simple acts of unity will, in their thousands, come together to unite us and celebrate the lives of David and Alan. This is what David and Alan truly stood for.

Michael Haines and Barbara Henning

Far from being “buried by archaeologists”, Sir Jocelyn Stevens embraced us and shared our passion for heritage. Committed to quality, and irascible when it suited him, Jocelyn brought a welcome breadth of vision and experience to English Heritage. Most of us responded enthusiastically – though some were scorched by his insistence that only the best would do. He recognised the power of archaeology to change perceptions of the past and influence the ways in which we would live together in the future. The new Stonehenge visitor centre and the restoration of the monument to its landscape would not have occurred without his persistent advocacy. He was a firm friend to archaeology and his support was crucial as it evolved from a preserve of the few into the wider world.